Sierra Leone Faces Significant Obstacles in Establishing Rule of Law, HRSP Concludes

It's a country without major roads, traffic lights, bookstores, or even ancient monuments, but Sierra Leone "may be the most interesting place on earth," said law professor Tim Wu during his introduction to the Human Rights Study Project (HRSP) presentation of findings April 8. Perhaps most telling, as students involved in the Project found, the country lacked a strong legal system that would give Sierra Leoneans faith in their government and the rule of law.

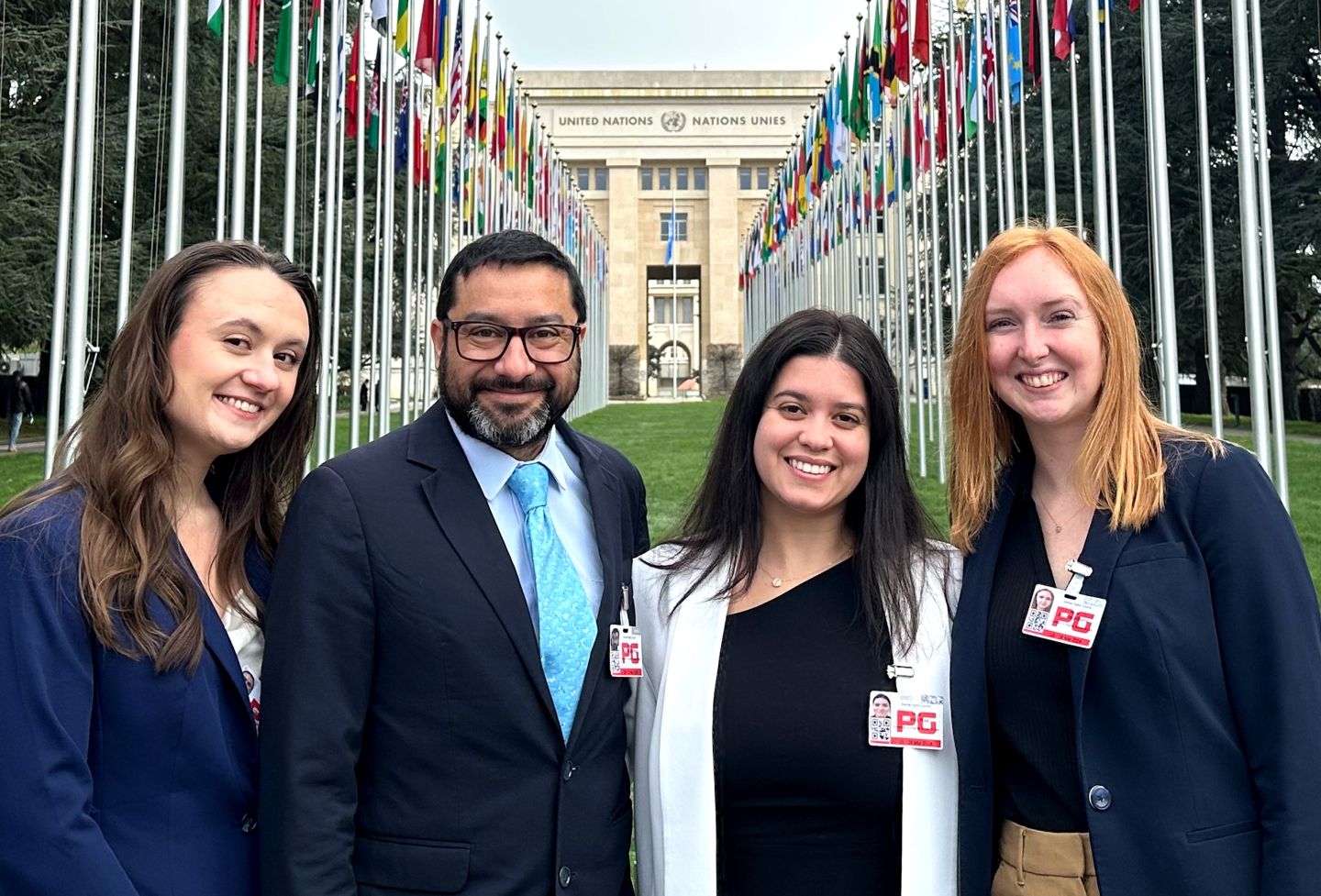

Each year, students who participate in the Project travel during their spring break to a foreign country to study human rights, with the aim of investigating a chosen topic and producing academic scholarship from their findings. The team hopes to publish its findings, which are based on their observations and interviews with U.N., Sierra Leonean, NGO, and Special Court officials.

In Sierra Leone, the group examined whether the ambitious idea of international justice can help end the cycle of violence that pervades Sierra Leone and much of Africa, where in many places, "any means of war is permissible," said Wu, who joined the trip to conduct research for his own scholarship; he is a faculty adviser to two HRSP members. The vast disparities between the United States and Sierra Leone became readily apparent when the group found that the only way to get to the capital, Freetown, was via helicopter-piloted by former members of the Soviet Air Force. Wu said the country, which recently emerged from years of civil wars, was a "fascinating place to investigate human nature."

Sierra Leone once served as a slave-trade outpost and later a British colony to which freed slaves were returned in the 18th century. HRSP member Art Koski-Karell explained that throughout its history, the country was used mostly for its resources, and never developed a stable agricultural sector or market economy. After Sierra Leone gained its independence in 1961, the country faced ethnic tensions, several coups, and corrupt leaders who had absolute power, all of which led to an intense mistrust of the government, Koski-Karell said. In 1991, then-Liberian President Charles Taylor and neighboring nation Burkina Faso sought to capitalize on Sierra Leone's economic instability and sent in less than 100 trained guerillas to take over the country, which helped spark a civil war. Taylor backed the rebelling forces, which had formed into a group called the Revolutionary United Front (RUF). In time it became clear the invaders were more interested in controlling the diamond mines, than in forging a political movement. Under international pressure, Sierra Leone held elections in 1996 despite the continued violence, electing President Ahmad Tejan Kabbah, but the turmoil continued until 1999, when the Lome Peace Accords provided for a U.N. peacekeeping force to enter the country. Within a year, though, the RUF and its allies started a war again.

"You had atrocities on a massive scale," Koski-Karell said. "The U.N. decided to step up its engagement, along with the British."

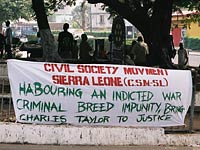

Under pressure, Taylor stopped supporting the RUF. By 2002 the civil war was declared over, and Kabbah was elected to another five-year term. Since then, Taylor has stepped down from power in Liberia and sought asylum in Nigeria.

Constitutionality of the Special Court

In constructing the Lome Peace Accords, Sierra Leone granted blanket amnesty to everyone involved in the civil war, said second-year law student Jenn Deleonardo, who focused her study on the constitutionality of the Special Court under the Sierra Leonean constitution. As guarantors of the agreement, the U.N. made a reservation that the amnesty would not apply to serious international humanitarian law violations. "Because of that, the U.N… could do something about the fact that Sierra Leone was not able to prosecute anyone," she said.

Kabbah requested international assistance in prosecuting war criminals, and the U.N. Security Council passed a resolution authorizing negotiations to create the Special Court. Sierra Leone and the United Nations signed a treaty in 2002 to form a "treaty-based court," different from those formed previously in places like Rwanda or Yugoslavia. To establish the Special Court, the Sierra Leonean Parliament passed the 2002 Ratification Act, which is now being challenged by opponents-including defense lawyers for indicted war criminals and others who disapprove of the Act's methodology-on the grounds that the country's constitution mandates that the Supreme Court of Sierra Leone is supreme to all other courts. Many in Sierra Leone feel that a constitutional amendment is required to set up such a court, but amendments require a referendum, which would have been problematic to present while much of the country was still under control of rebel forces.

The Special Court can now write court orders and warrants in the same way as other Sierra Leone courts, and arrests likewise are made through domestic law enforcement. "Inevitably you end up with something that operates within the Sierra Leonean system," Deleonardo said. Still, "it's unlikely the Supreme Court will say the [ Special Court] is invalid because there is popular support for the special court."

But the widely praised Sierra Leone model becomes problematic if it is universally applied to other situations. "It's popular in Sierra Leone right now, but what if that changed? What if you moved it to a country where it isn't popular?" she asked.

If the Court indicts alleged criminals who have popular support-as with a former defense minister who is charged by the Court and considered a war hero among the people-and resistance to the Court grew, the model might lose the consent of the people and legitimacy as a democratic institution.

Prosecutorial Discretion in International Courts

International courts in part "function to develop international law," said third-year law student Chris Dunn, HRSP director. Without an international legislature, and because the treaty process is too cumbersome to codify specific norms, international courts and prosecutors set the benchmark for how international norms are applied in practice. "Prosecutorial function is the first filter through which indictments are brought," he said.

Because the Special Court in Sierra Leone only has a three-year mandate to conduct trials, the Court's rules of procedure have been revised to minimize the judge's preliminary review of the prosecutor's indictments. Dunn said a vibrant defense office might act as a structural restraint on prosecutorial discretion; the Special Court has done more to assist defense counsel than other international tribunals have in the past.

Dunn met with Special Court Chief Prosecutor David Crane, a former JAG School teacher who was appointed by the United Nations, and Deputy Prosecutor Desmond DeSilva, a British lawyer appointed by Sierra Leone. They originally issued 13 indictments, but two who were indicted have since died, and the others have been consolidated into three indictments against RUF, Civil Defense Forces, and Armed Forces Revolutionary Counsel leaders, who represent three of the main factions fighting in the civil war.

Dunn said there are some Sierra Leoneans who are dissatisfied with the narrow jurisdiction of the Court, which is limited to those who "bear the greatest responsibility"; there is some sense that this won't reach actual perpetrators of the crimes. With such broad prosecutorial discretion in place, as many as 50 people might meet the narrow jurisdictional standard, Dunn hypothesized, but Crane has said from the beginning he will try about 20.

Dunn said his paper would address how prosecutors see their role in the international system, and whether they take conservative stances on law or instead try to develop international law norms. In an interview with Dunn, Crane said it was incumbent upon international prosecutors to develop international law, and in fact he's the first prosecutor to indict on charges of recruiting child soldiers and forced marriage.

"They're just pushing the [boundaries] of what we consider international law," he said. Dunn said he was arguing for a paradigm shift-that commentators, scholars, and officials must also consider prosecutors and defenders when developing these criminal tribunals.

"At some level guilt isn't the issue," he said. "The issue is, who among the many, many people we're going to choose [to indict]."

The Special Court's Influence on Building a Rule-of-Law Culture

The Special Court can trigger change in the Sierra Leone legal system, third-year law student Varda Hussain suggested, but it won't be able to sustain change after the Court leaves without a robust initiative that seeks to link the work of the tribunal with that of the national judiciary and with civil society at large.

The tribunal is acting against a backdrop of a collapsed judicial system, so effecting change is especially difficult, Hussain said. Explaining the state of the Sierra Leonean judicial system, she related her experience attending a murder trial. Absent a transcriber, the judge took notes himself. The legal scene appears even more haphazard once you realize "laws in Sierra Leone aren't written down.

"There's no precedent you can point to, which can make for some interesting judicial decision-making," she added.

Although the majority of Sierra Leoneans favor the establishment of the Special Court, several people Hussain talked with expressed disappointment about the lack of effect the Court may have on building a rule-of-law culture. When asked what legacy the Special Court might leave behind, the Chief Justice of the Sierra Leone Supreme Court remarked, "they're going to leave us the building-that's it." He added that the only influence the Court has had on the national legal system thus far is that they plucked his best registrar out of the national judiciary for the tribunal.

Some lawyers and NGO officials she talked to were resistant to the idea that the Special Court should work more closely with the national judiciary, for several reasons. Many pointed to the lack of funding and short timeline of the Court as necessitating a narrower mandate; others thought a stronger push to link the work of the tribunal with the national courts might undermine the independence of the Special Court.

The Special Court's Outreach Section strives to promote the understanding of the tribunal's mission and procedures to Sierra Leoneans, especially those in rural areas, but suffers from a lack of funding. The Section published a booklet with illustrations showing what the Court does, but it was sparsely distributed. Although there was initial support for a more vigorous capacity-building project, the idea was dropped due to lack of funding.

Despite these hurdles, the Special Court may have an effect on the nation's culture of impunity. "It's a huge symbol to Sierra Leone that this sort of atrocity will never happen again," Hussain said.

She concluded that the real challenge was to figure out how to "link short-term reform with long-term impact."

Jurisdiction Over Child Soldiers

An estimated 7,000 perpetrators of war crimes in Sierra Leone were children, some as young as eight-years-old, said second-year law student Sara Shapouri. The rebel forces used children because they were easily controlled and seen as expendable; lightweight weapons also made it possible for youths to bear arms. When Freetown was invaded, children made up the first wave of soldiers, serving as a possible distraction to townspeople expecting men.

Children were threatened with death if they refused to join or obey, and they were often given cocaine through a cut on their temple to make them more brutal or desensitize them in battle. The RUF would often tattoo its child soldiers with the group's name for easy identification and so they couldn't return home, where they might face recriminations.

Once the war ended, children were included in a disarmament, demobilization, and reintegration (DDR) program, a rehabilitation of sorts originally designed to last six months but later shortened to as little as four weeks. UNICEF estimates that 5,000 children have been reunited with their families, while others have been placed in interim care centers or foster care. The Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission has gathered child soldiers' stories in closed proceedings.

Many former child soldiers are homeless, she said, and haven't had the benefit of DDR. "These are children that aren't getting any help at all."

Shapouri said the decision to allow the Special Court jurisdiction over children who were 15 to 18 when they committed war crimes has been controversial. A draft statute placed by the United Nations originally called for the jurisdiction in addition to trying the children in a different court, although the latter was not established. "A lot of people didn't like them having jurisdiction over children," she said. Although the chief prosecutor decided he was "absolutely not going to prosecute any children," Shapouri said the fact that he could has ramifications for international law. "I find it personally really disturbing," she said, adding that an international tribunal was not an appropriate mechanism for trying children.

"Even if [you recruit a child soldier] to protect your own community, it's still a form of abuse for children, and they can't go back to just being kids."

"Blood Diamonds" Foster Corruption, International Crime

Conflict diamonds or "blood diamonds" are used frequently in Africa to fund wars or political movements, and in Sierra Leone the practice has wrought havoc on the country's stability.

"A lot of experts think that Sierra Leone has the richest diamond mines in the world," explained second-year law student Brooke Purcell. "Diamonds are literally spread across this country. You can walk along and pick one up."

Sierra Leone mines its most valuable resource through alluvial diamond production-meaning no machinery or large investments are necessary. "The mines look pretty much like the California gold rush," she said. "You've got guys with mines and picks."

Diggers work for a cup or two of rice per day, and get 2 pennies for every rough stone they find.

Sierra Leone produces $300-400 million in rough diamonds annually, but only about $1-2 million worth of diamonds were exported legally during the war's height.

Purcell planned to study how legal issues contributed to Sierra Leone's inability to control its diamond trade and what makes the resource so vulnerable to abuse by people like Charles Taylor. She added that she had to take a step back from her plan. "The biggest issues facing Sierra Leone are not legal issues at all," she said. The lack of law enforcement has led 75 percent of the people to believe being re-colonized by the British would be the best next step. "It doesn't matter what the laws are on the books when those laws are not respected," she said.

The diamonds that should make the country wealthy instead are a source of government corruption. Purcell met with Anti-Corruption Commissioner Val Collier, who she called an "amazing man"; despite this, by everyone's accounts the Commission has been a colossal failure and hasn't prosecuted anyone, due to still-widespread corruption.

Like precious metals, ivory, or firearms, diamonds are the implements of international criminals or insurgents, Purcell said. They sell well on the black market, are hard to trace, have a high value for the volume, are easy to carry, and are produced in lawless areas.

Purcell said rule-of-law issues need to be addressed first or "the Charles Taylors of the world will keep on coming. Several people she interviewed alleged that members of Hezbollah and Hamas in Sierra Leone may be using diamonds to fund their organizations.

"International crime and international warfare have become a lot more sophisticated than international law," she concluded.

The Military and Enforcing the Rule of Law

The Republic of Sierra Leone Armed Forces (RSLAF) lost credibility during the civil war, and now lacks the support of people to help secure the country and enforce the rule of law, said Koski-Karell.

"It was a broken institution during the civil war," he explained, with soldiers who fought during the day acting like rebels at night. "The army would meddle in politics on a pretty regular basis."

The country, with the help of the international community, is now moving to professionalize the troops and shrink the current force of 13,000 down to 8,000-a difficult task since most of the country is unemployed. The armed forces has established mandatory retirement ages and standardized testing to start pushing out the older generation of soldiers. Reformers have focused on civil-military training, because they want civil leaders to run the RSLAF. The United States is spending $500,000 a year to teach seminars about civil-military systems and fund exchange programs to Ghana and the United States.

Yet a leader at the U.S. Embassy Koski-Karell interviewed warned, "If the U.N. pulled out tomorrow, there would be a coup in a matter of hours."

The military's equipment is in disrepair, they're short on uniforms, and communications in the country travels by bicycle. In short, Koski-Karell said, they have a long way to go to be considered an effective deterrent.

Police, however, are better trained, better equipped, have better leadership, and more governmental support. Security officials Koski-Karell talked to were hesitant to admit that the government is supporting the police while leaving the military out in the cold.

"What comes first? Democracy or a professional military?" Koski-Karell asked.

The question is especially important in an area wracked with tension: the Ivory Coast is currently facing rebel armies, one of which reportedly includes Sierra Leonean mercenaries; Nigeria recently arrested a group of military leaders conspiring against its democratic government; and there has been recent fighting on the Sierra Leone-Guinea border.

Although the people of Sierra Leone have a favorable opinion of the British military, their traumatic encounters with other armies, even those that were supposed to be helping them, have sown distrust. The nation currently hosts 12,500 U.N. troops, and will likely continue to host a large number of them, but Koski-Karell wondered at the implications for traditional notions of sovereignty. "The military must be a Sierra Leonean institution," he said, even if an international deterrent is currently necessary to keep the peace. It may help, he added, to restructure the military as a source of cultural and legal reform, and not simply focus on its firepower. "[National] self-examination must go on, both in the military and in the government," he said, "but it's not."

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.