A group of students at the University of Virginia School of Law is working to ensure that the migrant farmworkers who bring in the harvest — primarily apples and peaches — at farms across the Charlottesville region are being treated fairly and that farmers are complying with the law.

The Migrant Farmworker Project, which is run by the Law School's Latin American Law Organization, dispatches law students to migrant farmworker camps to inform the workers about their legal rights, observe working and living conditions, and to check that the workers are being properly paid.

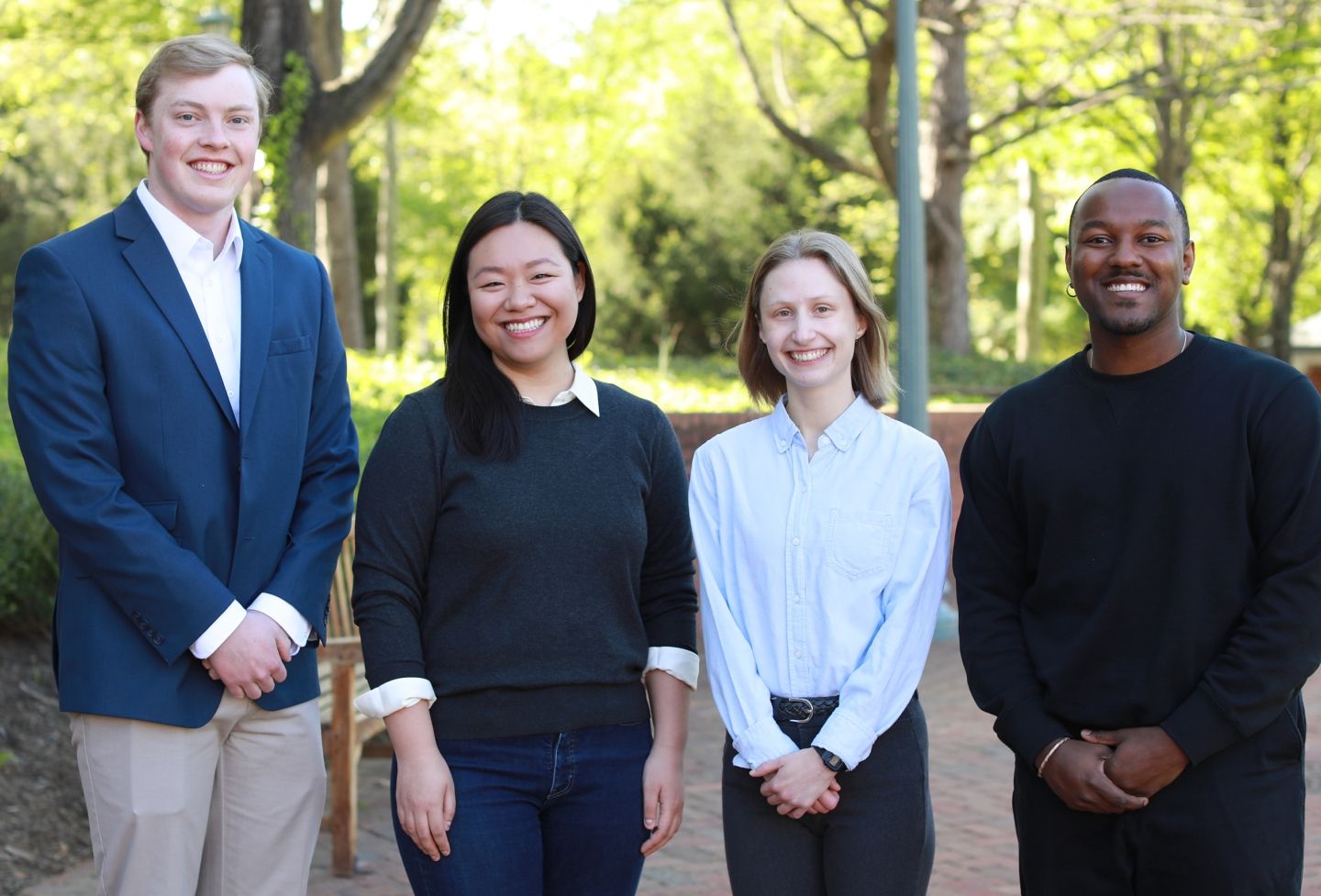

Second-year law student Eve Aguilar, a co-director of the project, said visiting the camps in her first year at Virginia Law helped "put everything in perspective."

"You arrive at law school and all of the 2Ls are stressed out, worried about on-grounds interviews and callbacks and jobs, and they're all wearing suits. I thought, 'Gosh, what have I gotten myself into?'" she said. "But then, going out to the camps and seeing the contrast of the cherry wood lockers at the Law School with the cinder blocks in the camps really helped me get back in touch with why I came to law school in the first place."

The students work in close cooperation with the Immigrant Advocacy Program of the Legal Aid Justice Center in Charlottesville, which takes action on behalf of the migrant farmworkers, if necessary. That action can involve lodging a complaint with government agencies, such as the Health Department; filing a lawsuit or reaching out to the farm owner to settle the matter.

"The No. 1 goal of the project is to make sure that migrant farmworkers who come to help us bring in the harvest in Central Virginia are treated fairly and given the respect that they deserve," said Tim Freilich, director of the Immigrant Advocacy Program and a 1999 Virginia Law graduate. "We want to make sure that all of the growers in Virginia who benefit from the labor of migrant farmworkers are complying with the law."

The law students essentially serve as outreach workers for Legal Aid by visiting migrant farmworkers in the field, gathering information and distributing workers' rights pamphlets.

"We want to make sure the farmworkers are being paid properly and that their housing meets at least the basic standards required by the law. Unfortunately, that's not always the case," Freilich said. "As a legal aid program, we have limited resources. So we appreciate the law students' work as a way to expand our reach and to disseminate our contact information and basic information about workers' rights in a way that we simply couldn't without their help."

Tyler Young, a third-year law student and a co-director of the project, said Legal Aid trains project participants about various related laws, such as the Fair Labor Standards Act and the Occupational Safety and Health Act.

"There's kind of a range of regulations that apply to migrant farmworkers, there are things like people not getting paid, people not receiving paychecks for their wages or people being paid in illegal ways — like they'll be paid by the piece of fruit they pick, rather than hourly — but then their piece wages won't add up to the federal minimum wage," Young said.

Checking out the farmworkers' living and working conditions can also be important, Young said. For example, the farmers are required to provide access to bathrooms while the workers are in the fields. Sometimes farmers will spray pesticides and require workers to pick crops before it's safe. In the camps, each worker is required to have a bed and the bed must be off the floor. And relevant legal rules and certifications have to be posted.

"Those are all kind of things we can look for on our trip because we have the ability to inspect the area based on how willing the people are to let us into their homes," Young said. "And we can also ask a lot of questions. How are they being paid? We might ask to see a paystub. We might ask if they have any complaints or problems."

The students primarily visit migrant farmworker camps at farms in the Charlottesville area, though they also travel to Winchester, which has one of the highest concentrations of migrant farmworker camps in the state.

Little information exists regarding how many migrant farmworkers are in Virginia. Nationally, there were 1.25 million hired farmworkers in July 2010, according to the Farm Labor Survey of the National Agricultural Statistics Service at the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Non-supervisory farm laborers earned an average $10.22 per hour, compared with $19.07 per hour for private sector non-supervisory workers outside of agriculture, according to the survey.

By visiting the migrant farmworkers' camps, the students are not illegally trespassing, even though the farm's owner may not have granted consent.

"There's actually a case that we [study] in one of the property books that we use in the 1L year that says migrant farmworkers have the right to invite guests onto a property on which they're living," Young said. "The property owners can't prohibit the farmworkers from inviting guests onto the property."

On occasion, the students have encountered some resistance from farm owners, they said.

"It is a little bit of a point of tension with farmers, presumably farmers who aren't following regulations," Aguilar said. "But it's not always confrontational. There have been cases where we'll get lost and the farmer will point us in the direction of the camp."

Many of the law students who participate in the project speak Spanish, though it isn't a requirement.

"I got involved initially as a way to keep up on my Spanish — and I fell in love with the work," said second-year law student Peter Hilton, a co-director of the project.

Aguilar, who was already fluent in Spanish, said the conversations with the migrant farmworkers have helped sharpen her skills.

"I speak Spanish," she said, "but I didn't know the word for 'bedbugs' or how to say 'minimum wage.'"

Hilton said he expects his experiences with the Migrant Farmworker Project will influence his future career as a lawyer.

"Even lawyers whose careers will take them in a drastically different direction — it's always too early to describe decades in a single phrase, but I imagine I'll wind up doing corporate transactional work — need to be aware of the human element of their profession," he said. "I intend to make pro bono an important part of my life, but perhaps even more significantly, the MFP work is an extension of who I am, and it's that 'who I am' perspective that will touch on every aspect of my career."

Young said he likes the Migrant Farmworker Project because it is "highly effective at what it says it's going to do."

"We go out and we visit these camps and we gather as much information as we can and we put it into the hands of people who are empowered to do something about it," he said. "Are we reforming the immigration system in this country? No. But we're doing a small part that we feel is important and we're really where the rubber meets the road."

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.