HRSP Members Witness Revolution in Lebanon, Oppression and Hope in Syria

Although it's the size of Virginia and North Carolina combined and has a population of more than 18 million, Syria has for the most part managed to keep its doors closed to inquisitive human rights scholars.

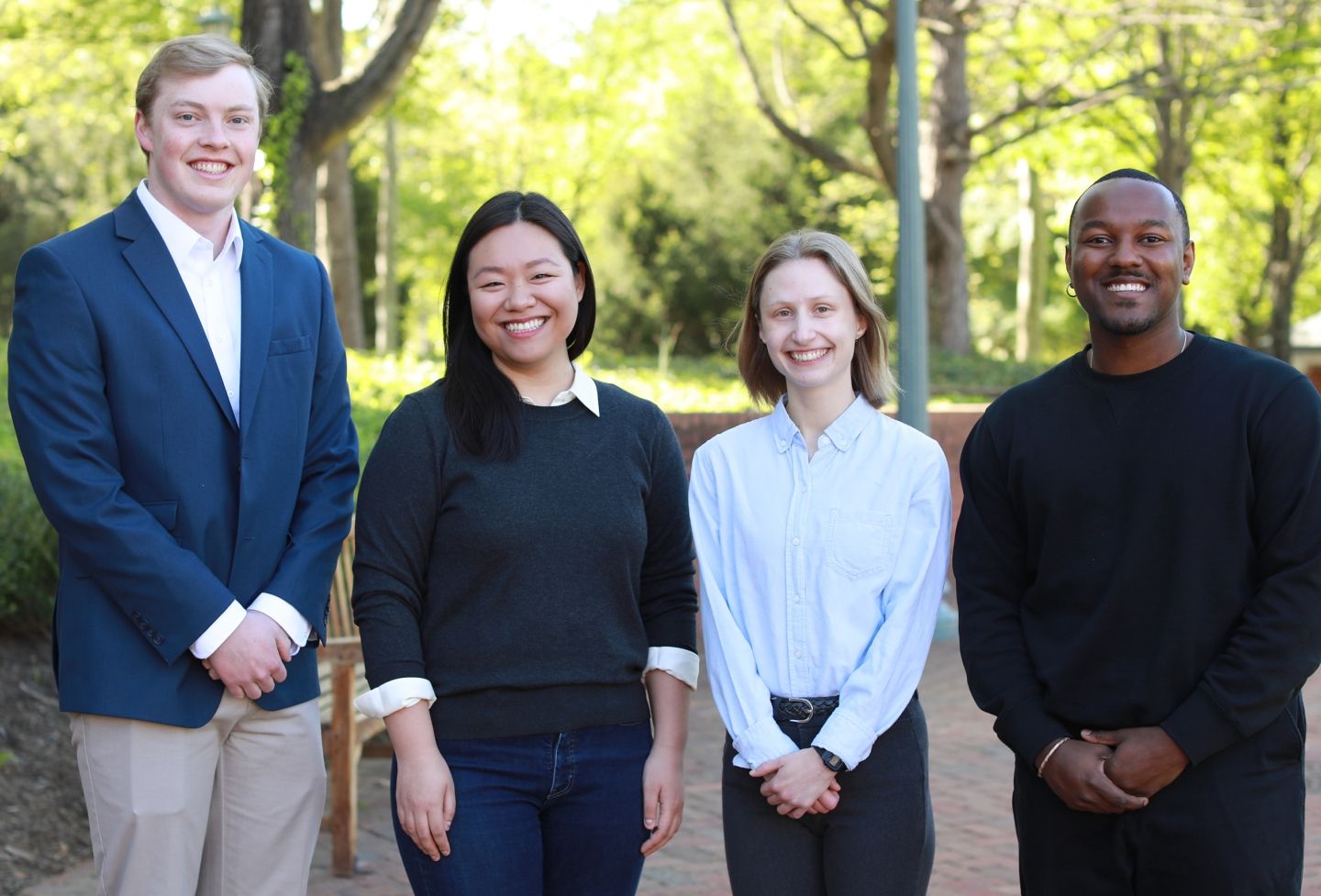

"The only way people found out what was going on with Syria was to talk to people who had left Syria," said second-year law student Frank Rosenblatt, a member of this year's Human Rights Study Project. Rosenblatt, fellow second-year student Jen Gilhuly, and third-year law students Heather Eastwood and Pat Lavelle found themselves in the middle of Lebanon's revolutionary Arab Spring during their field study of human rights conditions in Syria and Lebanon March 3-16.

Project members recounted their experiences April 7 at the Law School, showing photos of Lebanese protesters swinging banners that shouted "Keep Syria Out!" along with giant Pepsi-can graphics proclaiming Syria's expiration date as 2005. Wandering the streets during the confusion, Rosenblatt reported that Lebanese citizens would stop him and Gilhuly and ask, "Where's your Lebanese flag?"

Across Lebanon's eastern border, the students faced a different reception in Syria, with secret police, called the Mukhabarat, following them constantly. One lawyer offered Rosenblatt his business card, provoking a secret policeman to immediately step in.

"I just put the card away and acted like I didn't understand," he said. "In Syria we were really concerned that if we weren't careful with the people we talked to, they might get in trouble… There's just so many of the secret police that you can't ever escape them."

Project members found the two nations to be full of contradictions. Kind people are everywhere in Syria despite its authoritarian government and deep popular frustration with U.S. foreign policy, one student noted, while another investigated the desperate circumstances of Palestinian refugees in Lebanon.

The team originally considered Sudan for this year's trip, but the University would not allow them to travel to the war-torn nation. Prospects for their back-up plan, Lebanon and Syria, also appeared dim until the University qualified the ban by permitting travel there for compelling academic reasons. The area was an ideal destination, Rosenblatt explained; it was a "place where all of our interests really converged."

A Troubled Past

Syria's partial occupation of Lebanon mirrors the dynamics of the region's geography: Syria dwarfs its small neighbor. Syria's mostly Sunni central region has more in common with Amman, Jordan or Baghdad than with the Lebanese, Rosenblatt explained. Lebanon holds Shia Muslims in its southern regions, a faction whose political voice has increasingly been represented through Hezbollah. The Golan Heights, which lies at the crossroads of the two countries and Israel, is an Iraeli-held zone contested by Syria since the close of the Arab-Israeli War in 1967. On Lebanon's Mediterranean shore is Beirut, a French-English-Arabic polyglot capital that's highly westernized. More traditional Sunni areas occupy northern Lebanon.

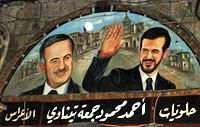

The Assad family, members of the Alawi religious minority community from the Syrian coastal city of Latakia, has ruled over Syria since 1971. When Syria intervened in Lebanon in 1976 against the Palestinians in Lebanon's civil conflict, Syria's Sunni population rebelled. Since then the Assad family has become more authoritarian. Presidential heir Bashar al-Assad assumed his position in 2000 without relaxing the family's grip on Syrian society.

Rosenblatt in particular studied occupation law as it related to the Golan Heights and Lebanon. "Occupation [in the region] was just an epithet there. There's no acknowledgement of occupation and there's no intention to follow any of the obligations of occupation set out in the Hague Conventions and the Geneva Conventions."

Syria's massive secret police bureaucracy and numerous rival divisions help keep the president in power by keeping checks on each other, Rosenblatt explained. He only found one dissident inside Syria, a novelist and reformer who criticized the president, calling him an "idiot" who did not deserve to be in power. The secret police tries to intimidate people like him-dissidents who seek to build a broader civil society movement and form professional organizations.

Just two years ago small groups protesting in central Beirut against the prominence of the Syrian secret police in controlling the Lebanese government had been jailed for their actions. This changed after former Lebanese Prime Minister Rafiq Hariri was killed in a bombing in downtown Beirut in February. Suddenly Lebanese citizens were calling for the Syrian military, which had been a presence since 1976, to withdraw. "While we were there, we witnessed a rally of a million people," Rosenblatt said. "Before this, there were other rallies that were expressing other political views, but it was clear that as we heard on the news about the diminution of the Syrian military and Mukhabarat in the region, that with that influence pulled away, people are finally able to speak out."

Syria and the Convention Against Torture

"Syria perfected modernizing medieval torture devices in the 1980s," Gilhuly explained-the rack, the tire, the German chair, "and other things involving electrical shocks."

So it was a surprise when the government ratified the U.N. Convention Against Torture last August. A trade agreement with Europe required Syria to take steps to improve human rights, "so one of the steps they decided to take was ratifying the Convention."

More predictably, the Syrian government declared that Article 20 of the Convention-providing for outside investigations of human rights abuses-doesn't apply to them.

The Convention is also undermined by the fact that Syria has been under a state of emergency since 1963, which places them under martial law. The reasoning is that "part of their soil is still being occupied, so there's still this aggressive force on their territory and they're still at war with Israel."

Under the emergency law the government can issue decrees, such as the one establishing the state security court, where political prisoners are tried. It's also illegal to work against the aims of the "revolution": unity, socialism, and freedom. "With this crime they can get anyone," Gilhuly said.

One decree required that to bring a torture claim in Syria under the Convention, you have to receive permission of the torturer's superior, which effectively blocks most claims. Under the Convention, when prisoners appear before the state security court, they can request a medical examination to investigate claims of torture. "Usually the judges just ignore these requests," she said. Lawyers working for clients who are processed by the state security court must submit their arguments in advance, but cannot meet their client until the day of the trial.

During the students' first full day in Syria, the head of the Syrian Committee for the Defense of Prisoners' Rights took them to a gathering outside the state security court. A year ago at the site, Arab and Kurdish students staged a sit-in protesting changes in employment law.

"The government does not like any organization, especially among students. They have a real fear of students organizing," Gilhuly said. In Lebanon, students "are the ones camping out, they're the ones riding up and down the streets waving flags."

As a result of the protest, several students were expelled from Syrian schools. Two were sentenced to three years, but Gilhuly found out recently they were given amnesty by President al-Assad.

Project members also met with Haitham al-Maleh, a Damascus human rights lawyer who is president of Syrian Human Rights Association. Al-Maleh was imprisoned for seven years for speaking out against the government, and he described his human rights work, for an organization that is illegal in Syria, as "swimming in darkness."

While the government removed the guts of the Convention, "people like Haitham use it to petition against the government." Al-Maleh and other lawyers employ the Convention to educate government and officials about torture and base some of their arguments in court on the Convention as well.

Human rights lawyer Anwar al-Bunni told the students that lawyers have to act like public relations agents in Syria. "Your job is to call attention to your client and make sure…people know what's going on, because the more attention that's paid to your clients, the better-off for them it will be," he told Gilhuly.

Al-Bunni encouraged Gilhuly and Rosenblatt to attend a demonstration calling for an end to emergency law and adherence to the Convention. Upon arriving at the scene, the students found a large crowd of young males screaming for the president, with al-Bunni nowhere in sight.

"The government had organized this as a counter-demonstration," Gilhuly said, bussing students to the site to overpower the human rights protesters. They found out later that al-Bunni was punched in the face, and his group of protesters had moved to a different location.

Working in Enemy Territory

Syrians working in Lebanon have been called "the other occupation" by some conservative Lebanese-American commentators, said third-year law student Pat Lavelle.

He focused his research on the rights of the estimated 200,000 to one million Syrians working in Lebanon, a country of only four million people, at a time when many Lebanese are calling for Syria's military occupation of Lebanon to end.

Lavelle highlighted a series of recent news stories on Lebanese animosity toward the workers. In early March, a group of Syrians were badly beaten by Lebanese nationalists in the southern city of Sidon; a week later, a Syrian shopkeeper was murdered in Beirut; and in early April, flyers appeared in another Lebanese town telling Syrian workers to leave or face unknown consequences.

"There have been a number of killings, beatings, threats, burned cars, burned tents, a whole range of things," Lavelle said, all aimed at a group that receives low wages for construction, janitorial, and farm work, and other physically demanding jobs.

"The fact that Syrian workers are there is also very important to Syria itself," he said. Syria's economic stability may rely on the free flow of workers to, and remittances from, Lebanon. Since the attacks on Syrian workers in the weeks following Hariri's death, an estimated 200,000 to 300,000 have left Lebanon. Lavelle wanted to know whether Syrian workers would stay in Lebanon in the long run, and whether their rights would change after the Syrian military's withdrawal.

"Although there's sort of a temporary dislocation with workers coming back to Syria, in the long-term, the workers are going to be there. Lebanon needs them for cheap labor and Syria needs them to be there" to reduce unemployment and to bring money into the country.

Lavelle also predicted their rights won't change despite the military's absence. One Lebanese labor activist told Lavelle workers would go to the Syrian military to informally resolve employment disputes in the past, and after the withdrawal Lebanese labor unions may be able to step in to organize workers.

"That seems like a potentially positive development," he said. "But largely the problem [with Syrian workers' rights] seems to be, not that the law is bad in Lebanon, but rather that no one obeys the laws that exist."

A 1994 agreement between Syria and Lebanon was supposed to ensure that migrating workers would be treated equally to citizens in both nations, but "the agreement isn't being followed in practice."

Lavelle met with top human rights lawyer and Beirut law professor Chibli Mallat, who explained that, according to the agreement, the Syrian and Lebanese ministers of labor are given sole authority to determine how the agreement is implemented, and that little had been done.

Fortunately, some leaders of the nationalist movement in Beirut calling for Syria's exodus from Lebanon recognize that anger should be directed solely at the Syrian military and government. As one politician put it at the massive rally the group attended in downtown Beirut, "our dispute is not with the workers-it is with their bosses."

Meanwhile it is important to remember that "the presence of Syrian workers in Lebanon is part of a larger economic situation," Lavelle said, involving widespread poverty and joblessness in Syria. Some efforts are being made by reformers in Syria to find avenues to decrease unemployment in the country.

The Palestinian Dilemma

Because Syria identifies itself as the leader of Arab nationalism, it treats Palestinian refugees better than Lebanon does, said Heather Eastwood. She noted that both countries border Israel, but have vastly different relationships with their neighbor. The U.N. Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East, which provides health care, education, and food to Palestinians, operates in both Syria and Lebanon, making the region an ideal place to study problems in refugee camps.

"Under Syrian law, Palestinians are almost as protected as Syrian nationals," Eastwood said. Refugees are allowed to carry identification papers and travel documents, and have other rights equal to nationals, except for citizenship and the right to hold public office. Palestinian camps and schools are almost indistinguishable from other Syrian neighborhoods.

Because of its larger size, Syria had fewer problems absorbing refugees in 1948 during the Arab-Israeli conflict, and fewer entered the country.

"Syria really has this ambition to reunite greater Syria, and so part of that is being the champion of the Palestinians and the bitter sworn enemy of Israel," Eastwood said.

Lebanese laws that govern the relationship with resident foreigners are based on reciprocity. "Since the Palestinian refugees don't have a nationality, they don't even get those protections," she said, meaning no travel or ID documents, and no employment rights. Rafiq Hariri, whose assassination spawned the Lebanese movement to expel the Syrian military, took away their property and inheritance rights a few years ago as well, even for those who already had homes outside the camps.

Eastwood met with Dalal Yassine, a woman who has her law degrees but is not allowed to practice because she is Palestinian. Yassine showed her Palestinian camps near Beirut, where schools have two kids to every chair and run twice a day. Running water is scarce, and shops don't always have the luxury of power to light their wares.

"The camps there are ghettos. What power they have there is illegal and not very safe," Eastwood said.

The Lebanese constitution assigns political power according to various confessional groups who prefer to maintain the status quo. The last time the census was taken, in 1932, 55 percent of Parliament seats were allotted to Christians, whose dwindling numbers since then have blocked more surveys. A census that included Palestinians could disrupt the balance of power.

The Lebanese also don't have the same Arab identity as Syrians have, Eastwood explained; they instead call themselves Phoenicians or Mediterranean.

"They really blame the Palestinians quite often for their civil war," she said.

Palestinians "are dead set on" returning to their homeland, a right which is accepted in international law for those who have fled armed conflict. Denying the right of return is considered a violation of human rights by the United Nations.

"Israel refuses to let them come back and has some good arguments for that," Eastwood said. "Immigration and citizenship laws traditionally are domestically decided." Israel is technically not the country Palestinians left, so conventions that guarantee the right of return may not apply. Citizenship also depends on loyalty to a nation's government.

"Israel has no reason to believe Palestinians would show any signs of allegiance or peace to the Israeli government," she said. Furthermore, allowing hundreds of thousands of impoverished Palestinians to return might wreak havoc on the Israeli economy.

Syria claims to be committed to the Palestinian right of return, Eastwood said, but when she was in Lebanon, "you start to understand …the Israeli line that the Syrian commitment to the Palestinian right of return really is nothing more than another endeavor to annihilate the Israeli state. Syria has been basically in charge of Lebanon and they've had all of these troops there, but they've done nothing for the Palestinians who are there."

Eastwood added that local integration seems unlikely. Palestinians have become a useful pawn for Syria, and the Lebanese don't want responsibility for the refugees because they blame them for problems with Israel, they are impoverished, and they don't identify with them.

Eastwood was surprised to hear the Lebanese and Palestinians claim that resettlement in a third country could be best, and many refugees told Eastwood they would go to America or Australia if they could because conditions are so poor where they live.

While visiting the camps during the mass protests in Lebanon, Eastwood said, no one there paid attention to the demonstrations or their portent.

After she left the camp area, Lebanese citizens told her, "This is the most important day in Lebanese history ever." When she asked them whether it would help the Palestinians, they replied, "It won't mean anything for them."

Rest for the Weary

The students spent a few extra days touring Syria and Lebanon, including a trip to the ancient city of Palmyra. At that oasis town, the group sat down to a meal, while the restaurant owner brought out a bottle of wine and played American soft-rock hits. "We toasted to peace in the Middle East," Eastwood recalled.

Gilhuly praised the Syrians she met-strangers and human rights activists alike-for their hospitable demeanor.

"We heard that all the time — you are welcome in Syria.' The people were just incredible." she said.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.