International Human Rights Claims Affirmed with Sosa,But Questions Remain

The Supreme Court left the door open for prosecution of international human rights violators in U.S. civil courts and reaffirmed prior lower court decisions with its Sosa v. Alvarez-Machain decision, according to a panel of legal experts who spoke at the Law School Sept. 10, but the future of such litigation remains unclear without legislation dictating a framework to decide such cases, some panelists argued. Others contended that judges are applying a narrow vision of the statute and it is safer to leave it out of the hands of Congress, who might be overly influenced by special interests in crafting legislation.

"The standards [articulated by the Supreme Court] are way too vague to guide the potential litigants," said law professor Curtis Bradley, arguing for more detailed legislation to guide such claims. If you want multi-national companies to be subject to greater regulation for their conduct in other countries, he added, determining the proper standards through piecemeal litigation against such companies "is the absolutely worst way to do it."

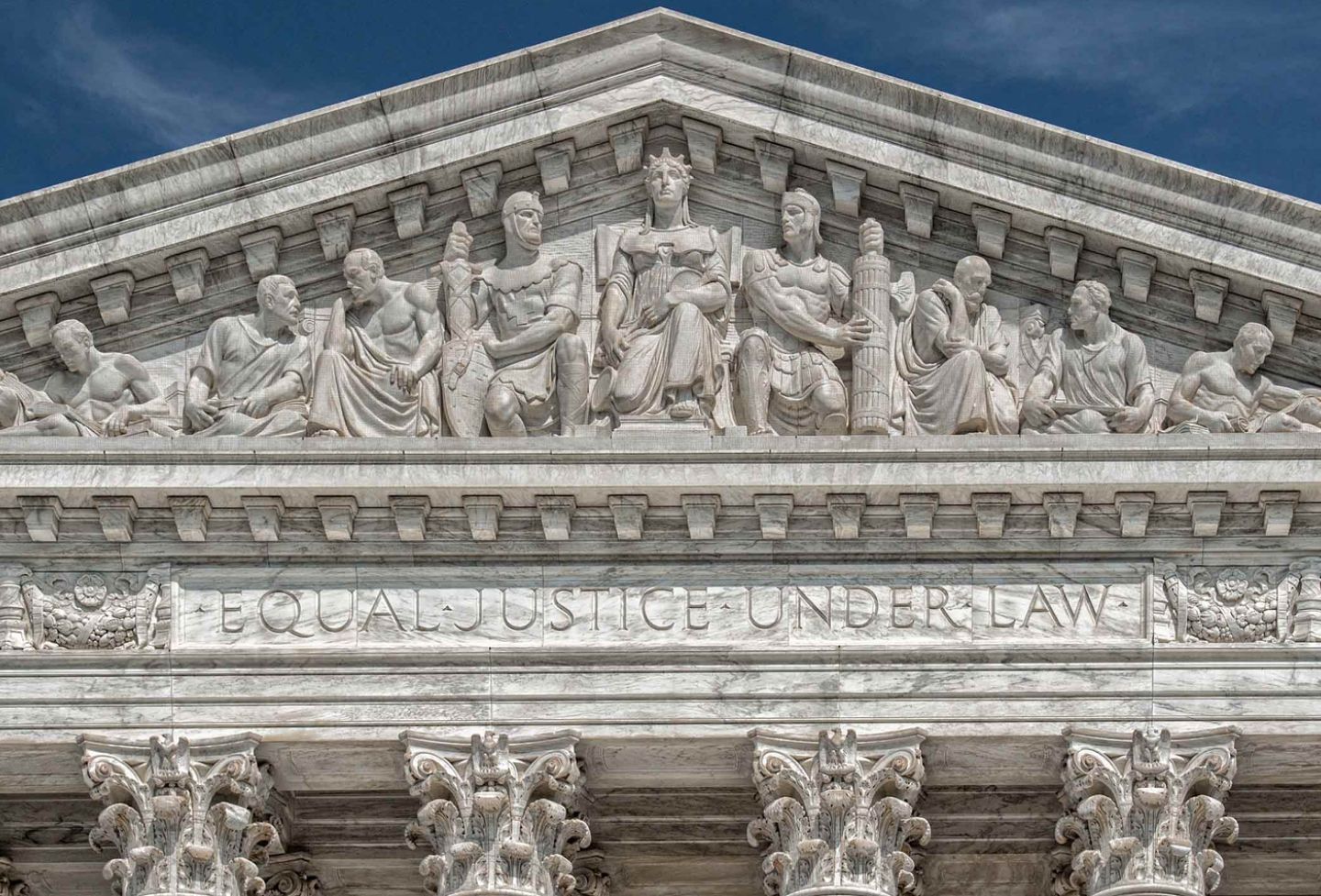

In the past 25 years, aliens' claims against human rights violators have been decided under the Alien Tort Statute (ATS), a once-obscure 1789 law granting jurisdiction to U.S. federal courts over "any civil action by an alien for a tort only, committed in violation of the law of nations or a treaty of the United States." Once used to combat piracy, the law was revived in Filartiga v. Pena-Irala, heard by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals in 1980. The case concerned the torture and murder of a man by a Paraguayan police official, later spotted by the murdered man's family on the streets of New York City, explained panel moderator and law professor David Martin. The court found in favor of the plaintiff, ruling that ATS gave them jurisdiction in the case because the litigant violated customary law. The U.S. State Department at the time agreed that the law of nations supported norms against torture, Martin said. The case opened the door for still more cases, and "several of those did result in judgments for the plaintiffs," he said. Since then, complexities have cropped up, as questions arose over whether the statute is just jurisdictional or whether it creates a private cause of action. The stakes increased when victims of human rights violations filed lawsuits against corporations working abroad, asserting they were responsible for crimes in places like Burma, where California-based Unocal contracted with the government to help build an oil pipeline; in clearing its route, the government allegedly used forced labor and relocated citizens. With corporations in the picture, "the prospect was open for some major verdicts that would be recoverable," Martin said.

In their last term, the Supreme Court took the Sosa case, in which Mexican doctor Humberto Alvarez-Machain claimed he was illegally arrested and detained by the United States and Mexican national Jose Francisco Sosa. Accused of keeping a DEA agent alive while he was tortured and eventually killed, Alvarez-Machain was later acquitted by a U.S. judge for lack of evidence. He sued the U.S. government under the Federal Tort Claims Act and Sosa under ATS. The Supreme Court came down in the middle, rejecting jurisdiction over Alvarez-Machain's claim, but more accepting of other ATS tort claims. "Their language is, I think it's fair to say, Delphic," Martin chuckled, leaving the Court's decision open to interpretation.

Bradley, currently on leave working as Counselor on International Law in the Legal Adviser's Office at the U.S. State Department, said he liked some aspects of the decision. All nine justices agreed the statute was just a jurisdictional provision, and he applauded their discussion of the history of the statute.

"There as a lot of cautionary language in the majority opinion," said Bradley, who emphasized he was speaking in his own capacity at the event. This may have indicated an attempt by the majority to "impose some sort of a brake on the expansive developments." For example, the opinion acknowledges the meaning of the phrase "law of nations" has changed dramatically since 1789 and could not have been anticipated in its current incarnation by the Congress that passed the statute.

Bradley said he had some problems with the way the opinion made a leap in logic in applying the statute to human rights cases today. When Congress enacts a statute it "does not enact an entire jurisprudential landscape," Bradley said. The decision, he explained, is also overly optimistic about whether the cautionary language will impose restraint. The Supreme Court used the same standards for judgment as the Ninth Circuit, but made opposite conclusions about the validity of Alvarez-Machain's claim, Bradley pointed out.

Although the opinion devotes a number of pages to explaining why Congress rather than courts should create causes of action, the majority could not bring itself to leave it to Congress to legislate with respect to human rights claims, Bradley said. He warned that with more than 600 federal court judges, each will have their own ideas about the statute. "I'm skeptical that with just that very general standard [provided by the Court], that it will really operate as a restraint," he said.

Allowing the ATS to be the vehicle to bring tort claims "has the potential and in fact does interfere with the management of foreign relations." The lawsuit's objective in ATS cases is to obtain, from one of the branches of the federal government, official condemnation or sanctions of foreign government actions, Bradley said, and such steps "are core parts of the conduct of foreign relations." Sometimes the political branches try engaging abusive regimes rather than sanctioning them to try to effect change. In some cases, cooperation in the war on terror may play a role in how the United States handles such regimes. The U.S. government often conditions sanction removal on whether the country has improved its behavior. "The litigation is not consistent with the general management of these issues by the political branches," he said. Foreign countries' protests against ATS claims have increased and the litigation threatens to undermine U.S. relationships with these countries, he said.

Referring to a case against companies that did business with South Africa's apartheid regime, Bradley said the country had already decided how to deal with apartheid-through a truth and reconciliation process. It shouldn't be up to U.S. courts to impose further sanctions, he suggested.

All the litigation is based on a one-sentence statute that "lacks any meaningful standards and limitations you would desire for this sort of legislation." The ATS doesn't even define whether there is a statute of limitations for such claims, he noted, or whether it extends only to state actors. This creates a predictability problem for corporations who need to know the risks of doing business abroad.

Rutgers law professor Beth Stephens, who filed an amicus brief in support of Alvarez-Machain, responded to Bradley's comments, noting that she agreed that the Supreme Court was wise to describe the statute as narrow. "I don't think one could plausibly make the argument that this particular statute applied today should be applied in a broad way." She said the lower courts have in fact applied the statute narrowly already. Broader claims have all lost or been dismissed. She predicted the Supreme Court decision will not change how cases are decided because their opinion is in step with previous lower court decisions. "The standard to be applied seems to be the standard that has been applied in the past."

Responding to Bradley's argument that corporations need better guidance to avoid ATS claims, Stephens said complicity with slavery, torture and genocide is not really questionable-corporations know it's wrong. When oil company Talisman contracted with the Sudanese government to clear areas for oil exploration, the government cleared out the people too, and the corporation knew the government would do that through egregious human rights violations, she said.

"I don't have any problem with saying the corporation should know it shouldn't be doing that," Stephens said. The same foreknowledge came to Unocal, whose memos show the corporation knew it was likely the Burmese government would commit human rights violations. Stephens argued that corporations defend against a lot of litigation, and "these standards as applied by the courts have been quite predictable."

There was some suggestion during Sosa's oral arguments that because other government branches hadn't proposed an amendment to ATS to narrow it, the Court was within its reach to determine such cases.

On the question of whether ATS cases affect foreign policy, Stephens said the problem of individual plaintiffs impacting policy is broader than human rights cases alone. Asylum cases (finding that a person will be tortured if sent home), antitrust cases, and cases where citizens get in trouble abroad all give the State Department headaches. "It's a cliché to say it, but that's the unruly part of a democracy."

She noted that the Sosa opinion said courts should show deference when the executive branch raises case-specific concerns.

Law professor John Harrison outlined one potential move ATS plaintiffs could make: they could bring cases in state courts, relying not on federal law that incorporates international human rights law, or on state law that does so, but directly on international human rights law. State courts are not subject to the jurisdictional limits the Constitution imposes on federal courts; they can hear cases in which all parties are aliens and there is no question of federal law, for example. If state courts conclude that international human rights law is sufficiently determinate and widely applied to count as law, they can decide cases under it, Harrison said. Congress would likely intervene if state courts began hearing such cases, and "we would get what we need in related areas, which is an act of Congress." Congressional action is desirable for several issues the courts have grappled with, such as the executive's authority to detain alleged enemy combatants, Harrison said. Until Congress acts, suits in state court-whether or not a good idea-would rest on a legally sound basis, he said.

George Washington University law professor Ralph Steinhardt, who served on Alvarez-Machain's legal team, said the Supreme Court's Sosa decision reaffirms the body of doctrine already in place. He recalled a frivolous case where a lottery winner who wanted her money in a lump sum sued under ATS, claiming denial of her money violated international law-"we need that case to disappear and lo and behold it does." He said the South Africa cases Bradley referenced are likely to be dismissed as well. The Unocal case, however, has strong standing under two frameworks: Article 3 of the Geneva Convention, which the United States is party to, refers to war crimes that can be committed by private actors, and the Genocide Convention also says genocide can be committed by private actors; secondly, the corporation and the Burmese government were so sufficiently enmeshed that the corporation can be found to be aiding and abetting.

Antidiscrimination statutes of the United States hold that when a private actor performs a public function, such as a corporation running a prison, the state can delegate obligations, Steinhardt said. "There's no part of law that says states can delegate obligations to private actors, then insulate those actors from private actions."

The Sosa decision was also consistent with a Supreme Court decision during the Spanish-American War in a case where the U.S. military seized Cuban fishing boats. The Supreme Court held that the fishing vessels were immune from seizure, thus showing that "international law is part of our law."

In a question and answer session, Stephens said she thought it may be best to keep legislation codifying ATS out of Congress as long as possible because "they'll only mess it up." If the Supreme Court had ruled against Filartiga, a movement would have formed to draft legislation, she added.

Steinhardt said that with the exception of Guatemala , no state has objected to the universal jurisdiction created by ATS because they don't want to put their arm around a torturer. Bradley injected that the United States has received "dozens of protests in the past few years" about the use of ATS.

When asked what he would think if the facts bear out that Unocal was complicit in Burma's use of forced labor, Bradley responded that he was sympathetic to the desire for redress, but objected to the case being decided without a more detailed legal framework. He proposed the issue be addressed in legislation or through a multilateral fashion with other countries. Stephens responded that some filings by the executive branch have egregiously been in service of corporations. If she thought they were equal partners, "it would be an entirely different landscape" when it came to legislation.

Steinhardt said corporate responsibility is not "imposed by plaintiff's bar out of control.

"The current corporate class understands there is a certain value in showing its commitment to human rights standards," he concluded, noting that the market alters corporate culture-not plaintiffs.

The panel was sponsored by the Human Rights Program, American Constitution Society, the Federalist Society, the J.B. Moore Society of International Law, and the Latin American Law Organization.

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.