Supreme Court Designed to Help Americans Make Democracy Work, Breyer Says

- Education: So Far, Good Will for No Child Left Behind

- Judicial Appointments: Ending Anonymous "Holds" Could Repair the Process for Making Judicial Appointments

- Constitutional Law: Patriot Act Charges Government With Balancing Privacy, Security

- Abortion Litigation: Right Winning War on Abortion in Court of Public Opinion

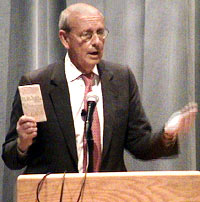

Supreme Court Justice Stephen Breyer called on a packed Caplin Auditorium audience of law students, faculty, and community members to participate in American democracy by being involved in public service during his keynote address at the Fifth Annual Conference on Public Service and the Law Feb. 28. The Constitution makes public participation key to a working democracy, Breyer asserted. "We in the Supreme Court don't make [democracy] work. Our job is to help maintain a system where you make it work."

As the years pass after law school, "it's harder and harder to remember that Roscoe Pound [an advocate of social advocacy in law] called our profession a profession imbued with the spirit of public service," Breyer said. "It's so easy to say when you're in class and so hard to do when you have a family and have bills to pay and are there in the law firm day and night thinking about being promoted." But "if you are nothing but a private practitioner, maybe you are not even one."

Appointed to the Court by President Clinton in 1994, Breyer focused on the meaning of the Constitution and the need for a vocal public to discuss the most difficult issues democracy faces. Breyer said he was still in awe of his newfound position, and joked lightheartedly about his special duties as one of the longest-running junior justices in Court history. "I've been the junior justice for 10 years," he said, joking that in the Supreme Court conference room, "If somebody knocks on that door, it is my job to open it. The other day somebody knocked and they had a cup of coffee for Justice Scalia. I thought that was going a bit far."

Interpreting the Constitution becomes "a steady diet" for justices, he said, who cover such ground more commonly than other judges. Breyer outlined the key elements of the Constitution's framework: it creates a rule of law, establishes a democratic form of government, has a horizontal (among federal branches) and vertical (between states and the federal government) separation of powers, protects basic human rights, and "provides a degree of equality and respect under the law."

Breyer described the thrill he still gets from seeing a diverse audience gather at the Court. "The miracle of this county is that so many different kinds of people from so many different points of view are in that Supreme Court chamber, resolving their disputes under oath," he said. "And what I'd like to point out is, that that didn't happen by magic."

Breyer, a former Harvard Law School professor, said he liked to teach three cases that he felt showed the uniqueness of the American Constitution. In Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), Cherokees who owned land in Georgia that was guaranteed to them by treaty were pushed off the land by Georgians when gold was discovered on the property. The Cherokees sued, but the Supreme Court sidestepped the first case. Later a minister from Massachusetts helped the Cherokees and was thrown in jail for not swearing an oath of loyalty to Georgia's government. He sued in Wister v. Georgia, saying Georgians had no right to throw him in jail for being on Cherokee land, which the Native Americans had rights to govern. Justice John Marshall's Court agreed with the plaintiff. "That is the case of which supposedly President Andrew Jackson said, 'John Marshall has made his decision, now let him enforce it,'" Breyer said. Jackson sent federal troops to the land to evict the Cherokees, sending them to Oklahoma; the trail they marched became known as the Trail of Tears.

In the second case, Cooper v. Aaron (1958), the governor of Arkansas had blocked a schoolhouse door, denying blacks access to the school and disobeying Brown v. Board of Education's order to end school segregation. "You could have had 9000 judges signing opinions, but how is that going to get the opinion enforced?" Breyer asked. But President Eisenhower sent troops to Arkansas "and this time it was in fact not to defy the Supreme Court but rather to enforce the court order."

He deemed the third case, "take your pick — Bush v. Gore, prayer in schools, abortion — all show that the people accept the Court's decisions. People feel very strongly about the cases, but the great untold story about Bush v. Gore, is that there's no story to tell about the enforcement," he said. "It is accepted that that will be followed, as will prayer in schools, as will abortion, as will many other cases that are highly controversial, and cases in which I cannot prove that I'm on the right side nor can anyone else prove that they're on the right side. There is a lot to be said on both sides of virtually every controversial case in our court."

"Perhaps the country has learned something after 200-some-odd years, because there is no question that those cases will be enforced," he said. "Millions of people have internalized the importance of following the law — that's the rule of law — not the document."

People learn to follow the law by court cases, by learning from teachers, and by how people act and the consequences of their actions. "It's in the public realm where, in fact, the lesson is learned," he said. "The thrust of the document is democracy."

But not everyone agrees with that, he said. Breyer met with Justices O'Connor and Kennedy a few weeks ago, and talked about surveys from students, who said the most important part of the Constitution was free speech

"What's at the heart of this document is a form of government where people govern themselves," he contended. He pointed to the arguments over privacy that have emerged as computer technology has made every action easily recordable. "How do we legislate in that area? What kind of laws ought we to have?" he asked. The debate in the public realm has been voluminous, as seen in everything from American Bar Association committee discussions to newspaper columns, Breyer said, and, the more that have an opinion, the better.

"I say 'wonderful' — wonderful because change comes out of that," he said of the debate.

"If you think we have the answer, you're wrong … what we try to do is not to answer such questions, but to set the guidelines… [we try] to interpret the constitutional provisions that will give the democratic process leeway." The Supreme Court can better define the parameters of the law when the people have "had a lot of input in a complex question like that one."

In deciding the recent Grutter decision that upholds the consideration of race in college admissions, Breyer said he weighed the opinions in the amicus briefs. The question revolved around whether affirmative action could be used under the equal protection clause of the 14th Amendment. "We ended up thinking it could be used to an extent," he said. Two possible interpretations were at stake: a purposive view that the clause was principally designed to help people who had been slaves to be integrated into society and to ensure there's no invidious discrimination, and the second interpretation: that "equal protection of the law means that the Constitution is colorblind."

"Both of those interpretations have quite a lot to be said for them and quite a lot to be said against them," he said. He carefully considered the U.S. Army's amicus brief, which said the service had many minority officers "and they do their job — but the military can't recruit unless those minorities get into colleges like West Point. Businesses said the same thing" Breyer paraphrased, "unless you allow a degree of affirmative action in elite law schools and universities, we are going to have a very difficult time maintaining a top-ranking executive cadre that reflects more than simply the majority race in the United States.

"I'm being told by people who know that if you choose the colorblind interpretation as the proper interpretation, we're telling you our institution is not going to work," he said. "And what we're really telling you is that the country is not going to work, because you can't have a functioning democracy where vast numbers of people in the United States think that this government is not ours.

"I'm saying that as I see this document, it creates a democracy that's supposed to work," he continued. The Supreme Court may maintain a system of democracy, but the people must make democracy work.

Breyer recounted that Pericles once asked the Athenians, "What is it that we say about the man in Athens who does not participate in politics?… We do not say he is a man who minds his own business, we say he is a man who has no business here."

Breyer asked students in the audience to not just be "the law-firm type.

"We are in a profession for a good reason that has a spirit of public service."

So Far, Good Will for No Child Left Behind

Panelists discussing the federal No Child Left Behind Act, which injects the national government into education issues to an unprecedented degree by requiring states to develop achievement and accountability standards, found little to dispute about its aims or methods.

According to Kent Talbert, Deputy General Counsel in the U.S. Department of Education and a member of the department's implementation team, "the very title sets forth the principle of the act: all students can perform to the same high standard. We shouldn't focus on averages, but the data on every group. The goal is to close the achievement gap between the disadvantaged and the advantaged."

The law recognizes the "natural tension" between national and state and local laws, particularly the tradition of local control over schools, he said.

NCLB sets 2013-14 as the deadline for achieving proficiency in reading and math through the eighth-grade level. Other goals are to provide school accountability and more options for parents, to retain local control, and to rely on scientific research and proven instructional methods. States will be required to give reading and math tests in grades 3 through 8.

"The impact of NCLB is the overall salutary effect of creating real urgency and a sense of crisis to improve student achievement. The negative effect is that it is a blunt instrument from the federal level," said John DiPaolo, executive director of for Partnership Schools of Temple University, an ambitious project by Temple to improve six north Philadelphia schools where only 20 to 30 percent of students read on grade level and 85 to 95 percent qualify for the federal free-and-reduced lunch program.

"The right level of pressure leads to progress; the wrong level leads to pathology," DiPaolo said. "There are two solutions to students not reading: one is to teach reading, the other is to cheat." He said he expects to hear more stories about schools cheating on tests in the future.

Happy that NCLB focuses attention on achievement gaps between high and low income and racial and ethnic groups, he said the solution is "to build the capacity to teach effectively. We have to make classrooms open so they are not just the private discretionary effort of one teacher. We have to get parents more involved in their kids' education."

Greater parental involvement was a recurrent theme with the panelists, as was the need to support teachers' command of their subject matter.

"If we knew how to solve the problem of lack of parental support, we would solve a lot of our problem," said Virginia State Senator Frederick Quayle, a member of the Senate's health and education committee. "Various strategies we've tried haven't worked. Students don't exert themselves when their parents don't require it."

"Schools have to learn to listen to parents," DiPaolo said. "Many did not have good experiences in school. Parents can be taught how to tell if their child's classroom is a good one. The premise [of the law] is that all students deserve to be taught by teachers who are highly qualified in the subject they teach."

Quayle said Virginia has a different take on the law than states not already reforming their schools on their own. "The basic problem we have is that we began our own education reform in the '90s. We've spent a lot of money on it and it works. Virginia today is number one or two as far as the accountability of its schools. The Standards of Learning were debated very heavily for several years before adopting them and then amended since then. We've got the SOLs and we're going to keep them."

Virginia officials are in the process of integrating No Child Left Behind into the SOLs, he said. The state is "asking for some waivers from NCLB because of some [SOL] provisions that we already have in progress that aim at the same ends."

He lamented that Virginia's educational bureaucracy is growing to collect and analyze the data that NCLB requires.

Had Virginia's reform strategy not been similar to No Child Left Behind, he doubted there would be enough federal funding provided to achieve NCLB's terms.

Hanover County Superintendent Stewart Roberson called NCLB "bold and proper" and said concerns with it are not over education per se, but about federal control and how to promote the change successfully. Reform mandates have not removed creativity from classrooms, he said.

Educational leadership research shows "that top-down change results at best in malicious compliance" and bottom-up change that lacks leaders' support results in "inertia" in the district, he said.

Noting that "50 wildly different tests are being developed by states," he wondered if the law would really lead to a relatively uniform minimum standard for academic performance across the country.

Again, it will come down to what parents do, asserted Talbert. "NCLB gives parents better report cards on their schools, but parents still have to use the data and make decisions on it."

Ending Anonymous "Holds" Could Repair the Process for Making Judicial Appointments

If the fault line dividing the panel discussing the politicization of the process for confirming federal judicial nominees is any indication, the prospects for making it less partisan are remote. Slatemagazine Senior Editor Dahlia Lithwick, who moderated, opened with the assertion that "This isn't about personalities. It's about a system that's profoundly broken."

Some politics is normal to appointments, according to Daniel Bryant, an assistant attorney general in the Department of Justice's Office of Legal Policy, but things are getting too nasty. "We got here because the Constitution has an interesting way of assigning responsibilities in the government. Separation of powers is not precise or pristine. It involves the branches looking over each others' shoulders… By design it's not efficient. It's a full-contact process with some low blows. A lot of the vigorous interaction is appropriate, but there's been conflict and bruising that's not consistent with the process as intended."

Neil MacBride'92, Chief Counsel to Senator Joseph Biden (D-DE), who sits on the Senate Judiciary Committee, agreed that the process could be more civil. "[Former North Carolina Senator] Sam Ervin once said separation of powers needn't mean war between the branches." But, he asserted, Republicans are distorting how bad things are. "President George W. Bush has had 171 nominees approved and only 6 rejected in the last three years."

Bryant contended that only 60 percent of Bush's nominees for U.S. Circuit Courts have been confirmed, whereas Carter had 93 percent, Reagan 89 percent, G.H.W. Bush 79 percent, and Clinton had 77 percent confirmed during their first four years in office. While the trend is clear, he pointed to the 17 percent drop for Bush as an even more partisan climate than previous presidents faced. MacBride called this assertion another instance of Mark Twain's famous aphorism about "lies, damned lies and statistics."

MacBride offered three reasons why appointments have become so politicized. "First, ideological litmus tests are being applied that were not formerly applied. Second, lower courts are not feeling so bound by stare decisis [to follow principles and rules set down in earlier decisions] and, third, the U.S. Circuits Courts of Appeals are now the end of the road for most litigants."

For U.Va. law professor Lillian BeVier, who was nominated for the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit by President George H. W. Bush in 1990 but never got a Senate hearing, the roots of the problem lie in the growth in law itself. "The law has grown exponentially, so the debate about what judging is gets more important. As we get more and more law and more cases, the ideological differences between judges get more meaningful. You wake up one day and you have the sense that judges are deciding everything.

"The stakes are high and lots of judges are acting as if they are political. They are acting on their personal beliefs and not on what the law says. So the stakes get higher and the game gets rougher."

Nan Aron, founder and President of the Alliance for Justice, didn't agree that such abstract causes are at fault. "I don't think the crisis stems from the process, but from George Bush's court-packing scheme."

There are almost 200 judges on the U.S. Circuit Courts of Appeals making decisions on behalf of a national population near 300 million, she pointed out. "These are very, very important people and they will be there for life. We've got a president like Reagan who is determined to leave his imprint on the judiciary. These people named by this administration have lengthy records of hostility to the rights we care about — clean air, clean water, choice, civil rights. These people must be stopped by any means possible."

"Whose choice should it be?" injected Lithwick. "What's wrong with the president choosing who he wants?"

"Bush wants to nominate people whose records show legal excellence, integrity, that they are truly impartial and understand the right role of a judge as opposed to a legislator," Bryant answered. "Judges should not be free to impose their political vision through their decisions."

"The fact is that despite the effort, and I believe it is a good-faith effort, to find people who are going to apply the law, all the nominations have become political now. The president is not going to appoint people who will make political choices for the other side. It's now a political fight and it's going to stay a political fight for as far as I can see," BeVier lamented.

"What's lost in the current debate is that in most instances this president has had his nominees confirmed," MacBride repeated.

Aron said politics should be involved in the nominating process. "It was envisioned as a political process. Republicans see judicial nominations in terms of results. They've done this for decades. They want people who will carry out their agenda for them. They want people like Scalia and Thomas. Democrats see [nominees] in terms of patronage, rewarding people who helped in the campaign. This administration has not played fairly the way Clinton did. He knew the Senate had a co-equal role. Bush treats the Senate like a stepchild."

"Not to put too fine a point on it," Bryant commented.

Lithwick asked what one thing could be changed to improve the process.

"The process needs to be more transparent," volunteered BeVier. "Most of what goes on goes on without the public knowing it. People don't know how important it is to Sen. Biden when the Alliance for Justice weighs in. Why don't we just elect the judges and be done with it? but of course we can't because they have life tenure."

Foremost among the obstacles to a nominee is the Senate's tradition of allowing senators to anonymously put "holds" on a nominee and suspend their consideration, Bryant said. A bill introduced by Sen. Charles Grassley (D-IA) requiring senators to state their reason for the hold within two days of placing it got only eight co-sponsors.

"The Senate has a 200-year history of delaying change," MacBride observed. Asked later why there are not simply votes on nominees, he explained, "that requires jettisoning 200 years of Senate tradition. We've never done it that way. There's a whole waterfront of important issues that come before the Senate that never get a chance to be voted on."

"The device of the filibuster and other obstructions are here to stay," said Bryant. "I would push for a more open marketplace where nominees get full debate and the Senate votes them up or down."

"Nominees don't know what's happening with holds," said BeVier. "I was stunned when my nomination lapsed and I found out why. I think the anonymous business has to stop."

Macbride compared the process to dating, where evasive answers are not reassuring, and said nominees "need to be ready to speak at length about their views on constitutional interpretation."

BeVier said she knows people who were approached about serving and said "no way, because they did not want their reputations trashed."

In the end, answering a question from the audience, MacBride agreed that reforming anonymous holds would be useful step.

Patriot Act Charges Government with Balancing Privacy, Security

Checks and balances help ensure the safekeeping of constitutional rights in carrying out the provisions of the Patriot Act, according to one official who deals with applications to spy on potential terrorists or foreign agents, but other participants in the Feb. 28 panel "Balancing Privacy and Security After September 11" said the Patriot Act goes too far in violating privacy rights.

"The problems that we're facing are at the heart of what this country's about," said Mark Bradley, Deputy Counsel for Intelligence Policy in the Department of Justice's Office of Intelligence Policy and Review. "The question is, how do we effectively protect the United States without violating our Constitution, especially the Bill of Rights."

Bradley said when he left work after September 11, he smelled the Pentagon burning. "I knew things had changed. They had changed dramatically."

Bradley said his office primarily prepares applications for the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Court (established by the Foreign Intelligence Surveillance Act, or FISA), which includes 11 federal district judges appointed by the Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. The applications usually seek permission for surveillance and electronic searches against U.S. and non-U.S. citizens who they have reason to believe are involved with terrorism or spying on the country. While the court has been active since 1978, the Patriot Act has extended the period of time subjects can be under surveillance, as well as the kinds of surveillance possible. After a FISA judge has signed off on the application, the application is certified by a high-ranking official, such as the director of the CIA or FBI, Secretary of State Colin Powell, National Security Adviser Condoleezza Rice, or Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. Additionally, four Congressional committees oversee the actions of Bradley's office.

"There is a regime in place that has oversight over this entire process," Bradley emphasized. "It's not some cabal sitting in the Department of Justice at Attorney General Ashcroft's feet."

The FISA court came into existence because of abuses by the intelligence community in spying on protestors and domestic critics of government, such as Martin Luther King Jr.

As a result of 9/11, the job has changed, Bradley said. He reads a large stack of threat reports each morning. "No one wants to be blamed for the next attack," he said. If they're wrong, there could be another attack, but "if we're wrong again, we could violate someone's civil rights.

"I have no doubt that [al Queda is] still out there and I have no doubt that they're going to try again," he said.

Panelist Casey Mattox, litigation counsel to Charlottesville's Rutherford Institute, said one of the biggest problems when discussing the Patriot Act is that most people haven't read it — not surprising since it's several hundred pages long.

"These are not evil people," he said of the administration. "No one is scheming… that [picture] doesn't help."

The Rutherford Institute has forged an alliance with the ACLU in fighting provisions of the Act, and also to challenge the United States' enemy-combatant policy, in particular the case of "dirty bomber" Jose Padilla, whose case will be heard by the Supreme Court because of their efforts. Mattox noted the Institute tends be considered a "conservative right-wing think-tank," and "no matter what we do we will always be known as such."

The usual conservative response to the Patriot Act is to say "I've got nothing to hide," so it's acceptable to spy, he said. Most people were ready to give up some rights after September 11, he said, and if the government had asked to temporarily suspend the Fourth Amendment, most would have agreed. Mattox said the Patriot Act essentially does just that.

Even if the current administration is acting responsibly, "things could change" with different elected leaders, he added. "My fear is that we will voluntarily keep handing power over to people who are trying to protect us," he said.

Mattox said he was most worried about the sneak-and-peek provisions of the Act, which give law enforcement authority in some circumstances to search a home without advance notice and delay after-the-fact notice. With the Act's allowance of roving wiretaps, the government no longer has to put taps just on a specific phone or computer; it could put a tap on a computer in Virginia's Law Library, for example.

"My largest concern isn't so much a privacy concern as the definitions of domestic terror," he added. For example, broad civil rights arguments could be considered domestic terrorism because the Act defines the term so loosely. If lawyers can find a way to twist meanings, they will, he warned.

George Washington University law professor and media commentator Jeffrey Rosen argued it was possible to strike a balance between privacy and security. He gave the example of the proposed holographic security screener that many complained about because it shows nude images of passengers passing through it. Rosen noted that studies show "it turns out people don't mind being naked at airports" if it means they don't have to wait in hours-long lines. Still, in response to complaints, Pacific Northwest Laboratories changed the program, scrambling the image of the naked body into a nondescript blob — for most of us an act of mercy," he joked. The new model "only focuses on guilty or suspect information," he said. "It's very effective in achieving its goal."

Rosen said he was convinced that all surveillance technology could be designed to look more like the "blob machine." As another precaution in air travel, the government's proposed data-mining program initially sought "total information awareness," integrating public and private databases, and including information on everything from bookstore receipts to telephone calls. The system was supposed to check if travelers fit the 9/11 terrorist profile, but there was no guarantee the system would even work, and no guarantee that law enforcement wouldn't use the system to prosecute low-level crimes. A coalition including the ACLU and the Rutherford Institute helped block the legislation allowing the system.

In contrast, Rosen said, Britain is so wired up it "resembles the set of The Truman Show."

The system that likely will be used instead, CAPS II (Computer-Assisted Passenger Screening), is "designed merely to authenticate that I am who I say I am." The system helps allay the fear of the "Nixon effect," where administration critics are prosecuted for no reason. With CAPS II, data cannot be forwarded to law enforcement unless the traveler has been convicted of a serious crime. "That is a victory for privacy," he said.

Rosen said he was not as worried about roving wiretaps, since they mostly allow the old rules to apply to new technologies, or the sneak-and-peeks, which can be used by law in a number of crimes. Instead, he's most worried about Section 215 of the Act, the infamous, not-yet-invoked provision that allows the government to see what books you're checking out from the library, among other things. He said even Laura Bush, a former librarian "was troubled by this provision."

Before, broad surveillance was only allowed if a suspect was believed to be an agent of a foreign power, but section 215 removed the requirement that the person be identified as a suspected spy or terrorist. Now if the government certifies he's a suspect, any data can be sought, "so theoretically you could have the Nixon effect."

Some lawmakers have proposed legislation to dampen 215, in particular the SAFE Act, which re-instates that the subject has to be a suspected spy or terrorist. It probably won't pass, Rosen said, because the argument that it could be used to go after low-level crimes "resonates with people." Many feel it might be useful to go after low-level crimes, as was done when Al Capone was convicted of tax evasion, if that's the only way to prosecute a suspected terrorist. "Resurrecting that proportionality argument … is politically difficult," he said.

Rosen instead proposed the "controlled-use model" used by the Germans, in which the government gets broad authority in surveillance, but can't prosecute people unless there's evidence of terrorism or a major crime. Rosen predicted lawmakers would reject this solution because they have been reluctant to differentiate between high- and low-level crimes. Furthermore, about 50 percent of the public thinks the Patriot Act strikes a good balance, and 20 percent think it doesn't go far enough. That leaves only 20 percent vocally opposing the Act, as Ashcroft is quick to point out.

"I wouldn't have any confidence that a President Kerry would endorse a SAFE Act," he said. He pointed out that most of the Patriot Act provisions were initially proposed during the Clinton administration.

Rosen said the courts cannot be entrusted to regulate privacy rights, citing their refusal to recognize private third-party databases. "The only time justices are really upset about privacy is when they can imagine their own privacy being violated," he said. "Constitutional values are being threatened, but constitutional law is completely inadequate to the task of regulating."

Congress is and should be responsible for imposing limits, he said. "What we need now is the will."

During a question-and-answer period, Bradley went into more detail about how low-level crimes could be useful in gathering intelligence. For example, if a Russian intelligence officer is committing fraud, he might be approached and asked if he wants to work for the CIA"or whether he would prefer they tell the Russian government he's been committing fraud on U.S. soil. The same principle might apply to terrorism cases, where someone committing fraud might lead to someone planning a terror attack.

Despite others' concerns over the division between criminal and intelligence divisions, "we're using these things for the purposes they're supposed to be directed at," Bradley said.

"If you're really concerned about this, then get involved in it," he urged. He pointed to other law graduates who have had an impact in government, including FBI Director Robert S. Mueller and the first general counsel of the CIA. Such jobs are high-pressure, but vitally important to security and preserving the Constitution. "I gave up sleeping well a long time ago," he said.

Mattox expressed concern over the fact that Rehnquist alone picks the judges; he along with the upper-level administration officials who certify the applications could constitute a collaborative regime. "That's maybe something I think that could be addressed," he said.

Bradley said in his experience the FISA Court includes a cross-section of judges who are not afraid to reject applications. "The FISA court seems to be very keenly aware of its jurisdiction," he said. He assured the audience that he, too, is aware of the issues at stake. "I'm of the view that if we violate the Constitution, we're losing the war on terrorism." He said Washington, D.C., puts a heavy emphasis on accountability, which was abundantly clear when FBI agents were called to task for not being more aware of suspected terrorist Zacarias Moussaoui's actions in the United States. His office is also aware that people who are vocal in their criticism of the U.S. government aren't necessarily worth spying on. "The real guys don't talk," he warned. "The real guys don't draw attention to themselves."

Mattox compared the political atmosphere after 9/11 to the overreaction caused by the Columbine shootings on zero-tolerance policies in bringing weapons to school. One boy took a knife from a girl who threatened suicide and hid it for fear of the school finding out; he planned to wait and tell his father that night. He was expelled when school officials found the weapon in his locker that day.

"When fear starts to drive policy, that's part of the problem," he said.

Right Winning War on Abortion in Court of Public Opinion

The left has been asleep at the wheel while the right is slowly but surely chipping away at abortion laws, some panelists alleged at the Conference's Abortion Litigation panel, while an attorney involved in litigation defending the federal Partial Birth Abortion Act and rights of pro-choice employees said the battle over early-term abortion rights was over, and only late-term abortion regulations are being challenged in court.

The right is "finding ways to chip away at this fundamental freedom," said Blake Cornish, Deputy Legal Director for Nominations at NARAL-Pro Choice America, pointing to the federal ban on partial-birth abortion and school board laws preventing abortion as a topic in schools. "The pro-choice majority in the United States is pretty complacent."

Most people don't know "how close Roereally is to being completely overturned," Cornish said. "We could lose it altogether." More than half of state legislatures are opposed to the right to choose, he said, and at least 12 states are likely to ban abortion immediately if Roe v. Wade is overturned. He identified 400 separate state laws enacted since Roe that restrict the right to choose or chip away at such laws. They make accessing abortion "humiliating."

The right has had a "conscious, long-term, patient strategy… to pack the courts with pro-life judges." He noted that the phrase "litmus tests" was first used during the Reagan administration, when the president would not appoint judges who were pro-choice. As a result, in the 32 cases in the Court of Appeals since 1992, judges appointed by Reagan and former President Bush were four times more likely to uphold a restriction to abortion rights.

People ask "how could this happen," he said. "The problem is that the law is not really settled in this area" because of ambiguous Supreme Court rulings. Planned Parenthood of Southeastern Pennsylvania v. Casey (1992) replaced the strict scrutiny standard of Roe with the "undue burden standard" in analyzing pre-viability restrictions on abortions. State regulations that protect potential life and maternal health are valid unless they impose a "substantial obstacle" in the woman's path. The definition of "substantial" has left judges some wiggle room.

Jay Alan Sekulow, Chief Counsel for the American Center for Law and Justice, agreed "there is not a lot of settled law" in the area. He worked on abortion litigation cases in the early 1990s that focused on free speech and the limits placed on abortions protestors; he is gearing up for litigation on partial-birth abortions, which will likely reach the Supreme Court, he said. "All of these cases tend to be on the margins."

When the partial-birth ban reaches the Court, "You could just ask everyone to leave, except Justice O'Connor," he said. "It's going to be a close call."

Sekulow predicted a potential Supreme Court case would center on the health-care exception, adding that he would be able to get testimony from a score of witnesses from esteemed health care institutions who have performed abortions themselves and believe partial-birth abortions are never medically necessary.

But "there'd have to be a lot of changes in the Court for Roe to be obliterated," he added, arguing that litigation is more likely to focus on partial-birth abortions and restrictions rather than a total elimination of abortion rights. Parental notification, for example, "makes sense." He recalled one case he worked on in which a school guidance counselor sent a minor across state lines to have an abortion without getting a judge's approval and without getting parental permission. She later had complications the parents had to pay for. The counselor "didn't even follow the law" by asking for a judicial bypass, he said.

Karen Raschke, Chair of Planned Parenthood Advocates of Virginia, said she would have killed herself if she had become pregnant in the pre-Roe South. She compared the demise of abortion rights to pulling a string of a sweater and watching it slowly unravel.

She suggested audience members understand how these issues are talked about in state legislatures. "I hate how women's body parts are tossed around the General Assembly," she said. She displayed charts used by lawmakers showing a partial-birth abortion procedure that didn't show the mother's head.

Partial-birth abortion foes were able to win because they changed the terms of the debate, she said. In her view, a DNX procedure is needed when a pregnancy goes terribly wrong. In Congress, "'partial birth' became a battle cry."

"At one time we described the bill as a classic bait and switch," she said. The bait was describing the fetus as a "Gerber baby" without mentioning the consequences for the woman, and the switch was the legislative language that described the procedure vaguely. By controlling the language of the debate and focusing on the most distasteful aspects of abortion, the right could triumph, she said. "Their territory is on later abortion and it's what makes us uncomfortable," she said, noting that the vast majority of abortions in the United States are not late-term cases.

"Unwitting" reporters perpetuated the partial-birth abortion terminology and "as a result of all those mistakes and all the unwitting participants, the few abortions we were talking about became all abortions," she said. "We did lose and we still lose in the court of public opinion … We're playing the same game now with emergency contraceptives."

In the question-and-answer session, Cornish noted that pro-choice advocates are trying to get legislation passed that would amend laws supposedly banning partial-birth abortion to ban just that procedure. The language of such laws, if upheld as is, would ban second- and third-trimester abortions, he said. "Under Roe, you do need an exception to protect the woman's health — and doctors or anti-choice advocates should not be making that decision, he added. "This health exception is kind of where the action is now."

Sekulow said challenges to the federal Partial Birth Abortion Act are proceeding in New York, Illinois, and San Francisco. In New York, judges are giving pro-choice plaintiffs a rough time for not handing over medical records of patients to medical experts testifying for the other side. Sekulow said the records are necessary to determine whether the abortions were medically necessary or not, while Cornish said the plaintiffs were trying to protect the privacy of women who are not plaintiffs in the case.

"Notice the debate primarily is the later terms," Sekulow said of the trend in abortion litigation cases. "You don't hear a lot of debate on first or early or second-term abortions."

Sekulow has also worked on a number of "conscience clause" cases in which doctors or nurses don't want to participate in an abortion procedure. They are "very winnable for my side," he added. A California jury awarded a nurse compensatory and punitive damages after she was fired for not helping with an abortion procedure that she was asked to assist in outside her regular unit.

Cornish classified the same cases as falling under the "denial clause" or "refusal clause." He said he thought individuals have rights in not performing services, but giving the right of refusal to HMOs is problematic.

"For us to allow one person to deny a service… I think is just so unethical," Raschke added.

Another stumbling block for pro-choice advocates was the announcement in 1997 by the American Medical Association that they favored a ban on partial-birth abortion, Raschke said. It turned out only two AMA members had made that official position, but the correcting statement didn't grab headlines the way the first announcement did.

Cornish noted that targeted regulations of abortion providers are forcing them out of business, especially in rural and southern locations. "Eighty-seven percent of counties in states have no abortion provider," he said.

Raschke said white and middle-class women would always have access to abortions, but "we'll have a lot more poor and underclass children because their mothers won't be so lucky."

Founded in 1819, the University of Virginia School of Law is the second-oldest continuously operating law school in the nation. Consistently ranked among the top law schools, Virginia is a world-renowned training ground for distinguished lawyers and public servants, instilling in them a commitment to leadership, integrity and community service.